If there’s a period in queer animation history we should be talking about, it’s the late 1960s to end of the 1970s. I’ve noticed that people understandably skim or skip this period entirely when discussing queer animation. This is also in part because the overviews I have found, like Business Insider’s wonderful 259 LGBTQ characters in cartoons that bust the myth that kids can't handle inclusion database and accompanying video, focus on mainstream children’s media. Admittedly, the 60s and 70s did not offer a significant amount of queer representation compared to other decades like the 90s. However, there were some notable animated works, especially in the 70s, due to the rise in adult and student films. As I am working on a book shedding light on the history of animated queer representation, one title in particular that interested me was the 1972 short film, How the Hell Are You? directed by Veronika Soul.

I first learned about this work on Letterboxd. This is in part thanks to the user MundoF, who compiled several massive LGBTQ+ lists on their account. While Letterboxd does allow one to narrow down results on a list, it is not exhaustive and, admittingly, a time-consuming task. What makes this task even more strenuous is that not all the films are correctly categorized - a film missing its appropriate genre(s) is most likely to occur - and this adds to the time it takes to research a particular work. When I began going through one of the lists, I started at the very beginning, from the 1910s onward. By the time I reached the 1970s, the number of independent works listed had grown significantly. While it can be easy to dismiss certain works, when I read the summary for How the Hell Are You?, I found it intriguing. Keywords like “collage” and “montage” stood out to me, and I decided to do further research. On The Movie Database (TMDB), the short was added onto that database in 2021, but there was little information about the work on that site, including no linked entry to IMDb and at that time, it was not even categorized as an animation. Thankfully, sites like Great Women Animators and the Canadian Women Film Directors Database (CWFDD) provided me with more information about Soul. On CWFDD, I even found a page on How the Hell Are You?. This included the only publicly available still I could find from the short and a possible clue on where to view the work: the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre (CFMDC). This was the best lead I had so far, as it suggested that the film was not lost but likely stored in an archive.

When I initially started my search, my greatest concern was that the film would be what people consider “lost” media. In general, I am personally against calling a piece of media “lost” unless there is strong evidence indicating it is truly lost. I’ve seen this perspective mentioned by other lost media enthusiasts as well, and I personally prefer a more optimistic alternative like “hibernating.” I define “hibernating” as media that does exist, but is not readily accessible on the Internet. This covers material stored in an archive, yet to be digitized, or owned by someone who hasn’t yet posted it. Fortunately, this short did fall into the “hibernating” category.

While How the Hell Are You? is not publicly available, Soul kindly granted me access to view it. Here are some aspects I can confirm about the film:

This work counts in the queer animation canon. It contains multiple queer characters and depictions of gender creativity. According to my current research, this makes it the first animated work in North America with explicit queer representation directed by a woman.1

The film has been digitized. Although it has not been fully restored, it is in viewable condition. I hope that under the right conditions, it may be screened again. It’s a wonderful short, representative of the political climate in the early 1970s, and would fit well in a program reflective of that period, especially if it tied into both the gay and sexual liberation movements occurring at that time.

The film was produced in color, not in black and white as I originally believed when I saw the still on the CWFDD website.

As discussed later in the interview, I believe the country has been classified incorrectly and that it is from Canada, not the United States. This gives it a unique distinction in animation history. Ideally, this article will help correct the categorization on CMFDC and other sites.

I want to thank Soul for taking the time to answer some of my questions related to How the Hell Are You? and her career as a whole. While this short cannot be viewed online, other works by Soul are available and I encourage readers to watch them.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Esther Bley: What made you interested in pursuing animation, and who are your animation influences?

Veronica Soul: Although I loved early animation like Steamboat Willie, I was not specifically interested in animation or filmmaking as a career. I should explain that when I went to McGill, I had already finished college, had worked as a children’s librarian at the Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore, spent a year studying in Paris, worked at The New Yorker magazine as assistant to the copy editor, and taught English part-time at Berlitz in NYC. So I was an older student when I took a year-long course in teacher training at McGill University.

While I was a student in teacher training at McGill University I had an opportunity to make a short film How the Hell Are You? and that led to work in animation at the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) where I became known as a cut-out animator. I did not do character drawings at NFB but worked with photographs and cut-out images. At NFB I became interested in the technology and the mechanics of filmmaking.

As an animator I often manipulated cut-outs freehand under the camera, so I especially admired the work of Lotte Reiniger for her elegant sense of motion. She had been invited to make a shadow puppet film Aucassin et Nicolette at NFB so I had the chance to see her working under the camera.

Although I was still a novice in animating, I was introduced to her as a cut-out animator. She always called me “the student”. She taught me how to use scissors correctly and how to cut a smooth curve by keeping the scissors hand stable and moving only the paper. It really improved my cutting skills and I used her cutting technique for my entire career. So in that sense I really was her student.

One great thing about freelancing at the NFB was the access to the technical departments and learning from the experts. The NFB was an ideal place to learn how to make films. Over the years I branched out to doing short fiction and documentary films, film poster design, film title design, and TV commercials. I was interested in all aspects of the film/video industry.

While at NFB I directed and edited a short fiction film End Game in Paris, that won Best Editing and Best Direction at the Yorkton Film Festival in Canada. The NFB was interested in giving filmmakers from other departments a chance to try working in dramatic film. I was lucky to be paired with Wolf Koenig, who had first hired me at NFB. He was the producer and cameraman on the project.

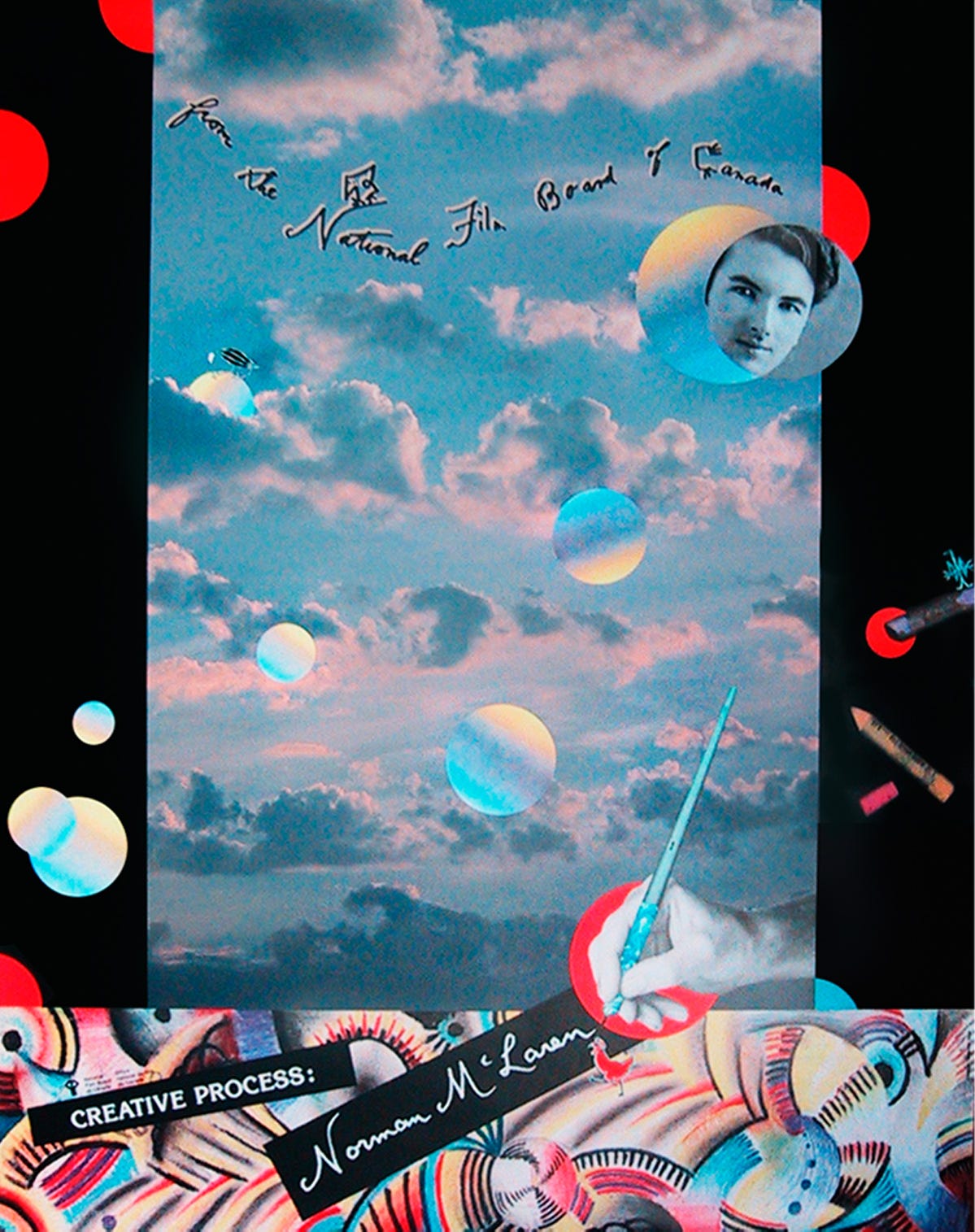

I also designed film titles and posters. My poster for the NFB documentary Creative Process: Norman McLaren received the 1st prize for poster design at the Annecy International Film Festival in 1991.

I continued to make independent films between jobs at NFB and commercial work. I think of those films as “mixed genre” filmmaking that combines stock footage, live action, photographs and print images. Karen Cooper of Film Forum described my later independent work as “film essay” which I think is a good description.

EB: Was there a prompt or other class guidance when it came to focusing on the story for How the Hell Are You? ? Were there other ideas you considered before you settled on the finished concept?

VS: By chance, one of my instructors asked me to make a short film instead of writing a final paper. I borrowed a Hi-8 camera from the McGill Media Center and shot a black & white pixelation Hi-8 film called Five-Cent Cigar. That was my first introduction to filmmaking.

I had been doing a lot of photography prior to coming to Canada and was spending my free time at the McGill Media Center where I learned to process film and make prints. I also began altering photographs with inks and markers and doing photo collage. At the end of the school year, Bob Pollard, the director of the Media Center asked if I would like to make a 16mm film that would represent McGill University in the annual Canadian Student Film Festival. McGill had not submitted any films for several years and he wanted to have an entry that represented McGill. He and his assistant gave me a crash course in film editing by projecting a short film called American Time Capsule by Chuck Braverman. It had become famous after it played on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour. The film is a rapid-fire montage of found images that are mostly 2 and 3 frames long, with an occasional 4 or 5-frame segment. They put the film on rewinds and scrolled through it to identify specific images. It showed me how the eye can see and retain images that were only 1 or 2 frames long, as well as how motion can be created between images.

Then they projected the film again, pointing out images that we had just looked at on the rewinds. We went back and forth like this a few times to give me a sense of timing in editing. They also showed me how to use a synchronizer and how to break down a soundtrack for animation.

American Time Capsule was a template for How the Hell Are You? and they suggested that I make a film for the student festival using a montage structure made with short segments. I had to present a script to the director and, if he approved it, the media center would let me use their camera and equipment to make the film.

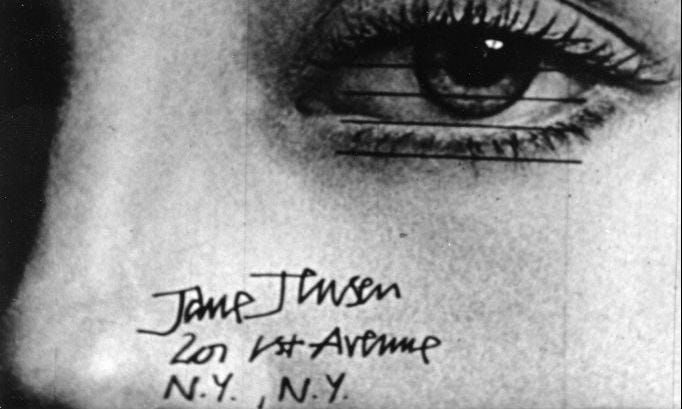

The director asked me to think about it for a few days and to come back with a script idea. I had always liked books like Studs Terkel’s books of interviews so I decided to do a selection of short excerpts from letters that a friend had sent to me about his travels over several years. The letters were like small artworks, written in a beautiful script. I also wrote additional text for the film and included a quote that was attributed to Tennessee Williams, although I am not 100% sure it was his. One segment of the text was based on a newspaper article. So there were multiple voices in the film. Making the film was a learning experience for me. I was able to experiment with different film and animation techniques such as drawing on film stock, scratching off film emulsion, drawing on photographs, manipulating images under the camera and pacing a film through editing.

I gave a rough draft to the director at the Media Center who gave his approval. I then made a final version which he also approved. I also had to show him some images in advance but, apart from that, he gave me free rein, which I now realize was very unusual. Without his trust I am sure I would not have had a career in film.

His investment paid off for McGill when How the Hell Are You? won first prize in the student festival. After the festival he called the NFB to find out who was the head of the Animation Studio. He thought I should call the NFB and make an appointment to show my work. At that time Wolf Koenig ran the Animation Studio. He was very excited to see the film and immediately gave me a short contract to work on project ideas. After that, the Film Board became my film school. It was a complete production facility with processing labs, sound stages and mixing theaters. I could see how other filmmakers worked and how they edited their films.

Although it sounds like an unlikely subject, my first film made at NFB was Tax: The Outcome of Income, an animated history of taxation in Canada made in 1975. Revenue Canada (the Canadian Tax Department) was interested in a film that was fresh and lively, something that would appeal to younger people. The film used a mix of hand-tinted and B&W xeroxed etchings and drawings from the Middle Ages through the18th and 19th centuries, combined with photos and stock footage from the NFB archives. It was nominated for a Canadian Film Award in 1976.

EB: How long did it take to make How the Hell Are You? ?

VS: I am not sure but it probably took most of the summer to make the film. I spent several weeks preparing images and a week or two shooting and animating with a 16mm camera mounted on a copy stand.

I wanted to shoot some live sequences to intercut with photographs and found images. I needed a guy to eat a hamburger for a scene near the opening of the film where the voice track talks about Walt Disney. The Media Center director was worried their 16mm camera could be stolen if I went out in the streets alone so he came with me to guard the camera. We hung out on a street corner downtown near an outdoor restaurant. After a few minutes a guy walked by who looked right for the part so we asked if he would like to be in a film if we bought him a hamburger and drink. He agreed so we shot the scene and got his contact info so we could invite him to the festival. I later heard that he was indeed in the audience at the screening.

I had been a DJ at the McGill student radio station during the school semester and learned to do sound recording and editing from the students at the station. The auditions for the voice track took place over one or two weeks.

A few weeks before the festival there were free sessions on splicing and negative cutting held at Sir George Williams University (now known as Concordia University). The event was run by the university’s technical staff and was open to any students entering the festival. It was held on two weekends. We learned how to use a guillotine splicer and how to edit our footage. A technician ran our edited films through a Moviola to check sync with our soundtracks. Then we learned how to do negative cutting and had our final prints made at one of the local film labs.

EB: There are pop culture references scattered throughout the short, why this decision? Additionally, the focus on the American Dream?

VS: I have always felt that the film is about finding one's identity in 1960s America, an era of great ferment for civil rights, gay rights, women's rights, etc. and pop culture reflected all of these things. I decided to open the film with a reference to Walt Disney whom I think can be seen as the essence of the American Dream. He showed that with hard work, ingenuity, and determination, you can be a success in America. With a small animated mouse he created an international phenomenon and a business empire that continues to this day.

EB: Has anyone (besides myself) reached out to you to discuss the fact that you are (likely) the first female director from the United States to have an animated short with explicit gay themes?

VS: No. I did not think the film was special or unusual when it was made.

EB: I've noticed on archive sites that How the Hell Are You? is considered a film from the United States, rather than listed as from Canada, or the United States and Canada. As the work was made and credited at McGill University, I was wondering why ultimately it’s solely listed as an American work?

VS: I think of it as a Canadian film, along with all the films I made in Canada. I am a dual citizen, so that may be why some sites list the work as American.

EB: As How the Hell Are You? was an early work in your filmography, what aspects of that process changed or remained the same compared to your later works?

VS: The montage/collage style of How the Hell Are You? became my signature style. It combined my interests in photography, collage, and live action material. I bought my own J-K optical printer and my later independent work was partly made on the optical printer. My last independent film used a lot more stock shot material and historical footage.

Although I didn’t know it at that time, cultural identity would become a main theme throughout my work. I think I was influenced by living in Canada, specifically in Quebec, and later by having opportunities to live in Asia, Africa and the Middle East.

EB: I’m especially a fan of your film, Interview with co-director Caroline Leaf. How did that short come about?

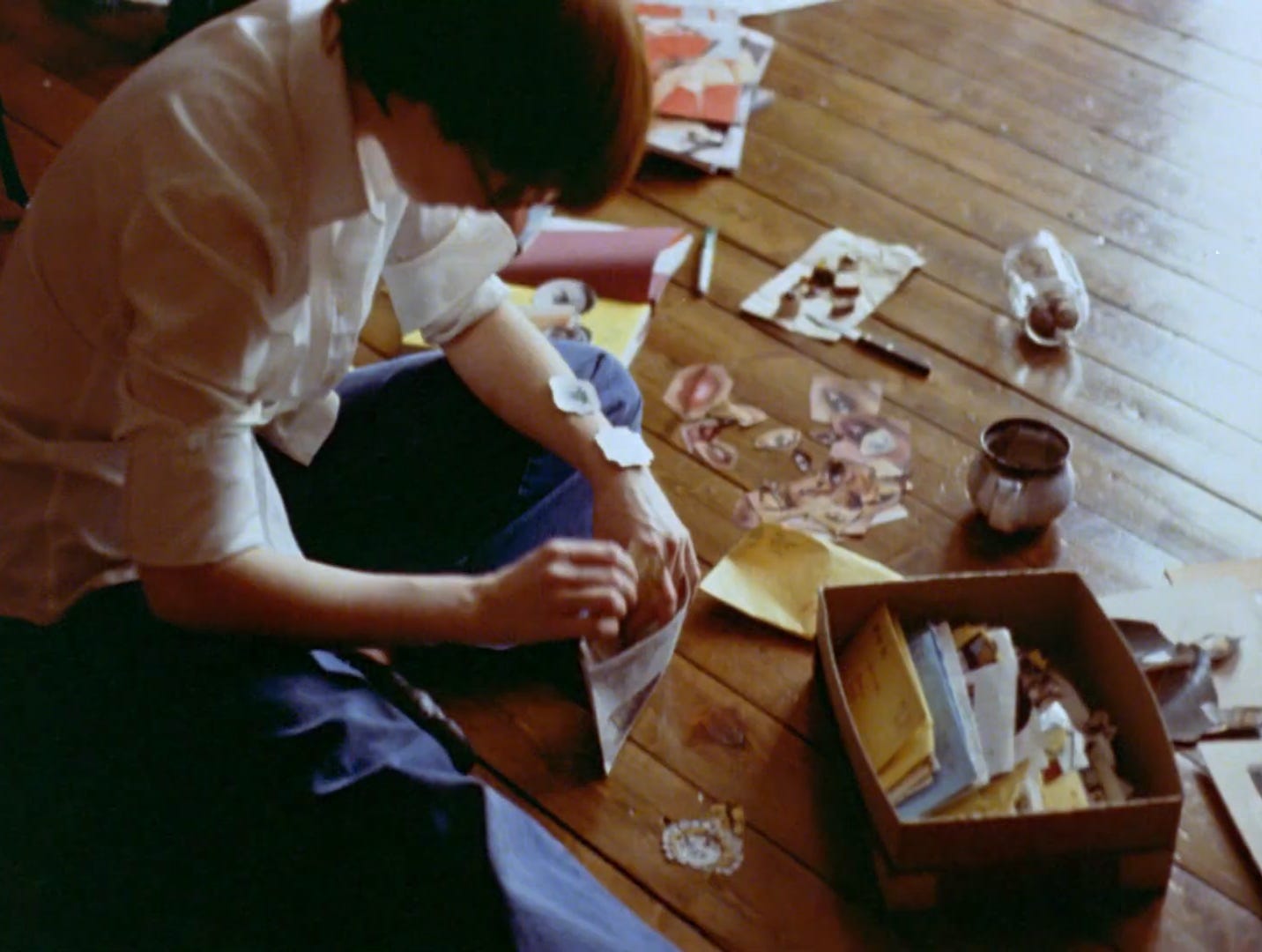

VS: Derek Lamb, who was the head of the Animation Studio at the National Film Board in Montreal, wanted to make a series of shorts about animators. They would be self-portraits. He asked if I would be interested in teaming up with Caroline Leaf to make a film about ourselves for the series. Caroline and I decided the film should focus on our work process. We did not know much about each other when we started, so we interviewed each other. That explains our title. Our idea was to show a day in the lives of two different animators.

Marie-Josée Saint-Pierre has written a book about women animators at NFB called Women and Film Animation: A Feminist Corpus at the National Film Board of Canada 1939-1989. The original French edition came out over 2 years ago. The English version was released on March 15th of this year. There is an entire section on Interview.

EB: I noticed on your website you did advertisement work, what led you to do commercial work and were there other animated commercials you did?

VS: I received many offers to do animated commercial work. I animated a TV commercial for Joseph Papp for The Public Theater’s Broadway version of The Pirates of Penzance. The artwork was done by Paul Davis who did all the posters for The Public Theater at that time. The commercial was a Clio finalist in 1982.

I also used cut-out animation for several TV show openings: The Brand New Illustrated Journal of the Arts hosted by John Houseman, The Morton Downey Jr. Show, and the children’s show Steampipe Alley which won a regional Emmy for design.

In Montreal I was hired by Foug, a local advertising agency, to make a TV commercial for the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts for their Pierre Cardin retrospective. It was the first time the Museum used TV to promote an exhibit. Pierre Cardin came to the gala opening at the Museum where the commercial was screened. The production house wanted to used one of Cardin’s original gowns in the commercial. For insurance reasons, the Museum could not let us borrow or handle the gown. So the production house hired a seamstress to recreate the gown which appears at the end of the commercial. I was told that Pierre Cardin winced when he saw the gown in the commercial. We thought it looked like the gown but he saw that it was clearly not his work. The commercial used collaged elements with digital effects combined with live action.

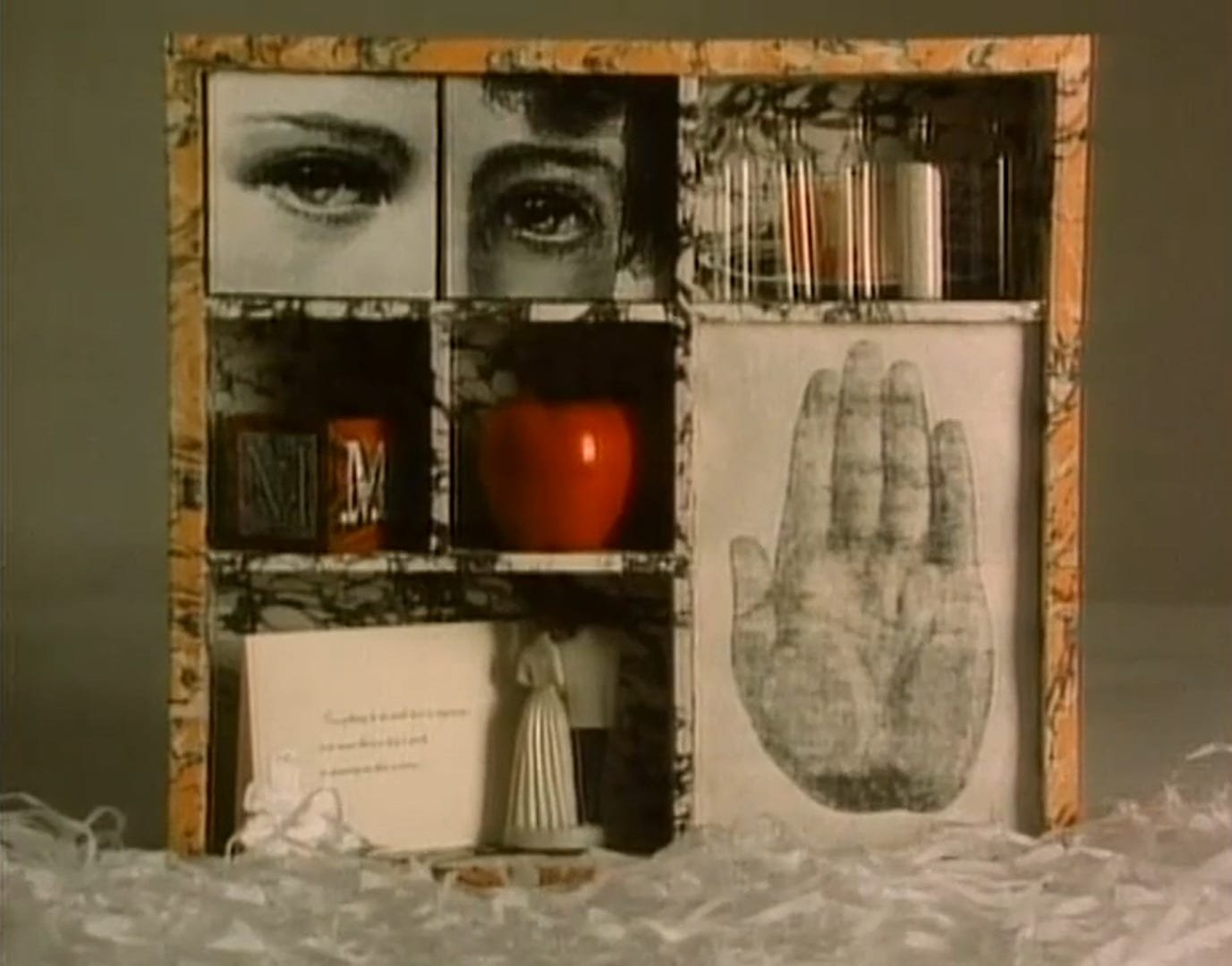

The New York Center for Visual History hired me to design and animate 5 shadow boxes for the documentary film “Marianne Moore: In Her Own Image.” It was part of the Annenberg-PBS Voices & Visions series on American poets. The boxes were supposed to be imitative of the work of Joseph Cornell. The entire documentary is available for free online.

I was sometimes hired to animate sequences for other people’s films. For example, I did an animated cut-out sequence for Lois Siegel’s A 20th Century Chocolate Cake (1983). The entire film is available online on Lois’ website.

I did the collage elements and cut-out animation for The B-52s music video “ROAM,” directed by Adam Bernstein. The animated squiggles were done by the animator Joey Ahlbum.

EB: Additionally, what work did you do for Sesame Street?

VS: I animated short segments for Sesame Street from 1994 to 1998. My signature style on Sesame Street was 3-D animation. I designed a box with rotating panels that contained the animation. YouTube has my animation for the “African Animal Alphabet.” It’s a soft image but will show you how the box with the panels worked.

EB: Are there any projects you are currently working on?

VS: I stopped working in film and animation over 20 years ago and transitioned to computer graphics and design. I am now officially retired but continue to do personal artwork and writing.

To view even more of Veronika Soul’s work you can visit her website, http://www.veronikasoul.com

Lotte Reiniger currently holds the distinction as the first female director to include queer, animated representation in her work. Coincidentally, Soul met and learned from Reiniger in the 1970s, which is discussed later in this interview. For those interested in learning more about queer representation in Reiniger’s work I highly recommend Dr. Lilith Acadia’s paper ‘Lover of Shadows’: Lotte Reiniger’s Innovation, Orientalism, and Progressivism.